|

.

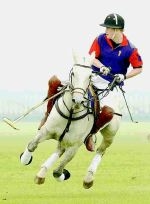

Polo: In B.C., it was once a sport for

cowboys, not just the idle rich -- a Victoria club keeps that

tradition alive

Saturday, August 23, 2003

'A polo handicap is your passport to the world," Winston Churchill once told a team of Oxford students, and I'm finally beginning to understand what the old boy meant. Watching eight men and their horses at play on a freshly-cut field just north of Victoria, it feels as if I've travelled to a different country, and far back in time. The red team's Number Four, its defenceman, Mike Adey, rides up to the ball and backs it, hitting a reverse shot to Steve Mann, the red's Number Three. Dan Pedrick, the blue team's Number Two, hooks Mann, and their mallets crack together as loud as gunfire. A scrum of riders gathers around, furiously whacking at the ball. Even though it's a cool grey afternoon, the players and their mounts are drenched in sweat. Then the ball squirts free. Brent Hoeppner, the blue team's Number One, winds up and belts it, a clean line drive, sailing past the scrum and the dozen spectators gathered along the sidelines. The riders turn their horses, erupt in a simultaneous "Eeyaah!" and thunder down the 300-yard field toward the red goal, turf flying around them, evoking for a moment the drama of a cattle roundup, or a cavalry charging into battle. Whenever most people utter the word "polo," their inclination is to pronounce it in an accent so plummy you could turn it into jam. Polo immediately connotes Empire and opulence -- Prince Charles, the Raj, champagne, silver cups, valets, hyphenated surnames. And in many places, polo is still like that: as the riches of the global elite have swelled, the "game of kings" has enjoyed a resurgence. It's more popular today in India and Australia than it has been for decades; despite Argentina's economic woes, polo still rivals soccer as that country's national sport. In England, young aristocrats continue to take up the game (perhaps following the lead of Prince William, who told his father that his life's ambition was to become a professional polo player). And in the United States, it's steadily growing in popularity at exclusive country clubs, where CEOs can assert their dominance atop the hierarchies of zoology and social class. But here on the sidelines of the Victoria Polo Club's practice field, the scene's a bit more down-to-earth. The referee toots a horn on one of the cars parked along the fence to signal the end of the final chukker. Elderly ladies set out tea and lemon cakes while regimental marches blare from a ghetto blaster. As the exhausted riders arrive, I discover they're all regular joes -- Adey's a dentist, Hoeppner's a fireman, Pedrick runs a B&B. "There's the cucumber sandwiches and all that stuff," Steve Hughes tells me, wiping his brow. "But you get out there, and there's nothing pretentious about getting horse manure in the teeth as you're charging down the field at 30 miles an hour with somebody trying to bump you off from the other side. It's real." Hughes, 45, is the last guy you'd expect to find on a polo field. He drives an excavator for a living, and with his long curly hair he looks like he should be in front-row seats at a monster truck rally. But six years ago, not long after he learned to ride, he went to an afternoon polo clinic taught by a pro visiting from Mexico, and he got hooked on the rush that comes from smacking a ball a hundred yards at a full gallop. Now, like many of the dozen hard-core members of the Victoria club, he plays twice a week. "I thought it was going to be this poncy little game -- 'Cheerio, nice shot, well done' -- but it's seven-and-a-half minutes of rodeo. It really is. Generally it's a safe game, but I've seen guys come down hard. Concussions, broken ribs. But you cowboy up, get back on and away you go. It's the original extreme sport, far as I'm concerned." Hughes is right. For nearly as long as people have been riding horses, they've been playing polo: the game itself is at least 2,600 years old (see "Polo's roots," D13). And as it turns out, here in western Canada, where horsemanship was once an essential skill, polo could be considered as much part of the historical landscape as cattle drives and calf roping. According to Polo, the Galloping Game: An Illustrated History of Polo in the Canadian West, by Tony Rees (Chinook Valley, 2000), the game was first brought west in 1883 by a British rancher who trained cowboys to play it in Pincher Creek, Alta. In B.C., military officers played it in Esquimalt and Victoria as early as 1889. British cattlemen, backed by investment money to raise beef for England's booming population, established polo in Kelowna and Kamloops; the poet Robert Service ("The Cremation of Sam McGee") played several chukkers with the Kamloops club in 1904. Players were so obsessed with the game that they travelled hundreds of miles to compete in tournaments: in 1896 a team from the Nicola Valley rode its ponies 50 miles to the Canadian Pacific Railway line at Spence's Bridge, then took the train to the coast and crossed by ferry -- back then, a journey of several days each way -- just to play a trio of teams from Vancouver Island. The 20th century changed everything. Polo's always reflected the course of human history, and what happened to the game in Vancouver proves it. A polo club was established in the city in 1913, but many of its key members -- especially those in the cavalry -- were mowed down by machineguns in the First World War. Though the game became popular with the city's elite during the Roaring '20s, it was killed again by the Depression and the Second World War. It didn't reappear again until 1953, at the Southlands Riding and Driving Club -- now the Southlands Riding Club. Tony Yonge, a Saanich farmer who now plays polo with the Victoria club (he was a member of the first Canadian team to play polo in England in 1973), fondly remembers the days at Southlands. The '50s were a gentle time; in the winter, when the playfields were boggy, the club would ride their horses and practise on the sands of Spanish Banks at low tide. But inflation swelled the costs of keeping ponies at Southlands, and the polo club relocated to Delta in 1971. A decade later, the Vancouver club disbanded, in part, Yonge says, because it became -- how very '80s -- "too rich and too rude. All the rich people hung together, and you can't have that in polo if you're going to play on the same team." A coterie of Vancouver players recreated the club in Delta for a few years in the late '80s and early '90s, but after one of its members bought property near Bellingham, they started playing south of the border, and continue to do so today. Polo is still played across Canada. There are 16 active clubs in the country: the largest are in Toronto and Calgary, and one with around a dozen members continues to play in Kelowna. But the game's practically disappeared from the B.C. coast. Fifty years ago there were more than a dozen clubs on the Lower Mainland and Vancouver Island; now Victoria is the only one left, and it just manages to hang on by remaining true to its modest roots. (The Victoria club does enjoy a bit of finery, though. On Sept. 6 and 7 its members will swap their jeans and sweatshirts for professional uniforms and compete with other Pacific Northwest teams for the Lieutenant Governor's Cup, a trophy donated to the club in 1983. For more information, see http://carriagehouseband b.ca/polo1.html) The Saanich peninsula still contains numerous small farms where people can keep horses, and every summer a few newcomers attend the Victoria club's annual clinics to try out the game. But Yonge -- who rides Polonius, a grandson of Triple Crown-winner Seattle Slew -- knows that the ever-rising cost of owning even a few horses will make it hard for the Victoria club to expand. "Horses need money," he says. "And your horse is 80 per cent of your game." Polo players consider their game the ultimate test of horsemanship, and it's easy to see why. Trying to hit a ball from a galloping horse is about as difficult as trying to hit a one-handed golf shot while riding a speeding motorcycle -- and a motorcycle with a mind of its own, at that. Not just any horse can play polo. In Argentina and India they're specifically bred for the sport, but in most other places, Victoria included, they're often former racehorses that couldn't win at the track. "They still have to be extraordinary animals," says Dan Pedrick, the Victoria club's secretary, and a part-time farrier (a blacksmith who shoes horses). "At the very least they have to be bred for athletic behaviour, and well put together." One chukker lasts seven minutes and the horses often run flat-out for much of that time -- two horses are buried on the edge of the Victoria club's practice field, felled by mid-game heart attacks. (Before anyone protests, remember this happened over the course of the Victoria club's 40 years of play.) Beyond their physical conditioning, horses also need to learn the game itself. Besides maintaining their composure with mallets and wooden balls flying around their head and legs, horses must learn to stop, turn and accelerate to a full gallop in an instant, and to "ride off" (bodycheck) other riders headed for the ball. Pros will often spend up to a year training a horse, and a "made" (game-ready) horse easily sells for several thousand dollars more than the trainer paid for it. Top-flight polo ponies can cost $50,000 and up. Argentines say a polo player must have presencia, a presence that inspires confidence and team spirit, and garra, the heart to fight back when down. Comprehensive medical insurance is a good idea, too -- polo players often wrench their backs or sprain their arms contorting themselves to make shots, and several Victorians have shattered their legs in high-speed collisions. But more than that, polo players need friends at the bank. Players switch to fresh horses after every chukker, so even in Victoria they need at least two or three, and along with the tack, the cost of stabling and game equipment imported from the United Kingdom, they often need a second playfield to allow the fairway-quality turf to recover. Fortunately, two of the Victoria club's members are farmers, and are such fanatics for the game that they've converted part of their fields to polo grounds. "Polo has always been exclusive. It's hard to play, and you have to marshall so many resources," Pedrick says. "That's not to say everybody who plays polo is rich -- there are plenty of cowboys who play polo. But the people who have money are necessary to the sport because it doesn't generate money on its own. It comes from patronage, and without it, polo would die." Because most people consider polo a pastime for the wealthy, it has difficulty being taken seriously as a sport. It was removed from the Olympics after the Second World War because of the cost of transporting the horses, and it never turns up on TV in this part of the world. (One of the few egalitarian things about polo is that men and women often play it equally well, and frequently compete in mixed teams.) "Polo has some serious problems with the way it's perceived by the public," concedes Pedrick. "People are intimidated about coming to a polo match because they think they're going to encounter a bunch of snobs. But believe me, every polo player in this neck of the woods really works against that." In Victoria, at least, it's possible to see polo for what it

really is: a game with a history and a culture as travelled and worn

as an old saddle.

See Also: Polo has its Roots in Ancient Warfare(sidebar) Ross Crockford is the co-author of Victoria: Secrets of the City, published by Arsenal Pulp Press. © Copyright

2003 Vancouver Sun | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||