Hacienda San Isidro: West of the Andes, South of the Moon

by Dan Harvey Pedrick

Additional photos by Naoko Yamamoto

Debajo de tu piel vive la luna…

—Pablo Neruda

Chile is a country of startling contrasts and rare beauty. With its towering Andean peaks, ancient forests and lakes, and endless South Pacific beaches Chile extends over 4,300 km (2,700 miles) along the southwestern coast of South America, a distance roughly the same as Pittsburgh to Los Angeles—yet its width never exceeds 240 km (150 miles). Its name does not eponymously derive from the notoriously fiery fruit of similar spelling and reminiscent shape but rather from the indigenous Mapuche word meaning, “end of the world.”

But the end of one world is just the beginning of another…

.jpg)

The geographical and historical heart of Chile lies in its Central Valley. It was here, in a fascinating mix of political intrigues, battles, earthquakes, coups d'état—and no small amount of Spanish, British, Irish and indigenous influence—that the modern Chilean state was born nearly two hundred years ago. Central to that struggle was Bernardo O’higgins, a native-born Chilean of Irish extraction for whom, like so many of us, life was a crazy-quilt of humiliating defeats, stunning victories, and unexpected outcomes.

Great Britain was deeply involved in the Chilean struggle for independence against Spain, which had fallen under the power of Napoleon. As the disillusioned Chileans turned their backs on the mother country the British Royal Navy provided military support and the model for Chile’s own maritime forces that exists to the present day.

Charles Darwin visited Chile in 1835 during his famous voyage aboard H.M.S. Beagle, which sailed along the Chilean coastline for fifteen months making intermittent stops along the way. While ashore he observed fossilized forests and shells high in the Andes which led to his famous Theory of Evolution.

Today, Chile is considered one of the great polo-playing nations owing to the efforts of British naval officers who, acting as the vector for the spread of polo globally in the late 19th century, diligently evangelized for the sport throughout the British Empire and beyond. A well established horse culture in an environment naturally suited for it provided the perfect matrix for the adoption of polo and the sport’s conquest of the South American Continent’s Southern Cone.

Chile hosted the FIP World Polo Championship in 1992, where it won second place, and received third place in the 2004 World Cup held in France. Chile won the FIP World Championship in May 2008, after beating Brazil 11-9 in the final game of the 2008 Polo World Cup in Mexico City.

The late Gabriel Donoso was probably the greatest polo player in Chile, and is remembered for having led the Chilean national team to win England’s prestigious Coronation Cup, awarded by Queen Elizabeth II in 2004, and again in 2007. Today, proximity to Argentina energizes the polo scene west of the Andes with horses and players of the best quality regularly participating in tournaments at all levels in Chile’s dozen and a half clubs nationwide.

- - -

Hacienda San Isidro is the oldest house in the province of Curicó and one of the best preserved estate mansions of the colonial era in the entire country. The house is surrounded by glorious gardens and polo fields. The hacienda is also dedicated to agricultural production and breeding of cattle, sheep, and horses.

The surrounding hills are abundant in vegetation and laced with historic trails used by the patriotic troops in the struggle for independence.

The present owners of Hacienda San Isidro are Felix Garrido Concha and his wife, Patricia Larson. According to Garrido, the first proprietor of what would become Hacienda San Isidro was local partisan and symbol of Chilean independence Francisco Villota (a compatriot of O’Higgins) who was administrating his father’s Hacienda Comalle as early as 1808. Villota ended up hung by his heels in the local village square by the Spanish colonial authorities in 1817.

One Jose Irizarri bought it next and subdivided the enormous property into various smaller holdings. One of these, site of the former Mill of Comalle, became Hacienda San Isidro. By 1842 the next owner had completed the construction that survives to the present day, a sprawling triple H – shaped edifice with a total of eight patios.

In 1918 Dionisio Concha Silva, great-grandfather of Felix Garrido, bought San Isidro as a new home for his dairy herd which he drove over the mountains from the adjacent valley of Colchagua. Since then four generations of the Garrido family have carefully and tenderly cared for the 2500 square meter home, each leaving their own unique mark on the celebrated mansion over the years.

Every corner of this sprawling patrician edifice transports the visitor to the past. In its many salons and rooms every piece of furniture and art object has something to tell about the lives and routines of Chile’s country dwelling landowners, their pleasures, their passions, and their trials. After years, decades, and centuries of weddings, baptisms, funerals, visits, and natural disasters, many significant artifacts—ranging from ancient weapons and tools to exquisite paintings and statues—are found within and on its walls. All this comprises an intimate testament of the past like no other that exists in Chile.

The dairy farm period of Hacienda San Isidro began in 1918 and ended forty-some years later when the profitability of the venture ebbed with the changing tide of market conditions. Two concrete silage towers still stand as monuments to that bygone time and a reminder that the farmer’s marketplace can be a fickle mistress. Presently the farm produces food for the global market including tomatoes, grapes, onions, cherries, melons, and apples. That market too, however, has shown itself to be subject to change without notice.

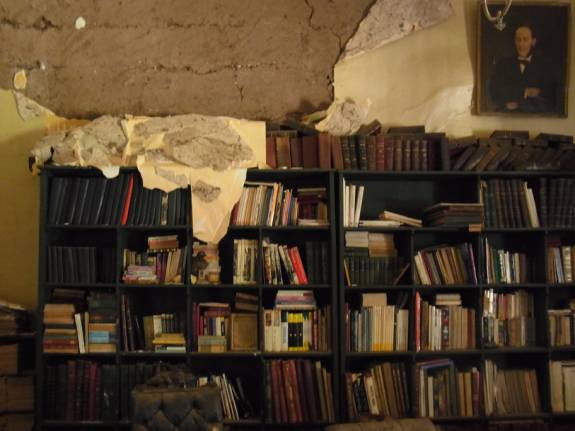

But the most disturbing changes of all recently affecting Hacienda San Isidro lie deep beneath the rich soil of its fertile fields in the form of tectonic plates known as the South American and the Nazca. These geological formations are engaged in a titanic rugby scrum thirty-five kilometers below the surface of the earth. Roughly every fifty years or so (only a couple of seconds in geological time) they produce an episode of violent shaking on the surface that changes everything. The cataclysm of February 27th, 2010, did extensive damage to the venerable hacienda structure but its nearly metre-thick adobe walls withstood the ultimate test of time once again, and remained standing. The family chapel, nevertheless, was completely destroyed along with many sculptures and paintings of rare quality.

The difficult and expensive process of restoration began immediately. “Walls and roofs were our first objective, obviously,” recalls Felix Senior. “We still have the library, the music room, and the chapel before us. It’s difficult and expensive, to be sure, but we are convinced that everything will be sorted out eventually and we have every intention to move forward with it. We are very optimistic and have many great friends who have helped us very much.”

Due to this sudden tragedy and the preceding vagaries of the international economy Felix Garrido and Patricia Larson decided to dedicate a wing of their home to tourism and included a boutique hotel in their restoration project. This would be accommodated in a dozen ensuites in the southeast wing, each notably different from one another and decorated with furniture and objets d’arts from their vast collection.

As Garrido and his sons, Felix and Rafael, had been playing polo passionately for years, an activity that included all aspects of the sport from breeding and training of horses to international tournament play, guests would be able to receive polo instruction at various levels and participate in a number of tournaments held on the estate’s playing fields throughout the season. Other activities would include trail rides on the sprawling estate with its historical O’Higgins Trail, traveling the wine route of the valleys of Curicó and nearby Colchagua (with its internationally acclaimed museum and casino), and relaxing in the pool and hot tubs. Other excursions in the development stage include trail rides, rafting, and fly fishing in the nearby Andes—all to be debuted on haciendapolosanisidro.cl .

The Garrido family introduced Polo as a family sport and important activity at Hacienda San Isidro in 1937, building the country’s first polo field south of Santiago. The Oscar Bustamante Letelier Polo Cup, which has been hosted for the last fifteen years by the Garrido family, pays homage to the region's prominent Bustamante family and especially to the father, the late Oscar Bustamante Letelier, who promoted the sport of polo in the region in the 1950s. The surviving members of the Bustamante family can count among themselves—aside from several ardent and accomplished poloists— distingushed artists, painters, architects, and writers. The awarding of the prizes for the Bustamante Cup is not only an opportunity to recognize and honor the winners of the contest but also to see and enjoy artistic works of the Bustamante family who create and present the trophies every year.

Responding to an invitation to experience South American polo west of the Andes we arrived in the small village of Teno, Province of Curicó, on a Friday afternoon in early March. The fully ripe late summer weather was lovely and languid and evidenced by many roadside fruit stands chock full of produce amid the frantic activity of the harvest.

Kayla Culbert met us in the village and escorted us to Hacienda San Isidro, about eight kilometres into the surrounding countryside. We were met there by her husband, Felix Garrido junior, Felix senior and his wife Patricia, and a host of family members, guests, and staff of all ages blended together in an undifferentiated friendly mob. Kayla had warned that there was some construction going on but all seemed well prepared as we were ushered into a charming and comfortable suite in the southeast wing where we dropped our luggage. She then herded us through the labyrinthine hacienda house to the bodega, where the local vintage soon washed away any lingering traces of road fatigue.

Kayla is adept at herding all manner of creatures—kids, sheep, visitors, horses, dogs—especially dogs. Born in Vancouver, B.C., she is completely at home in Spanish or English. Her multi-cultural background proved its worth time and again in managing the polyglot visitors passing through Hacienda San Isidro, not least ourselves.

I could not help but notice that young Felix was walking with a noticeable limp. “A freak accident,” he said with a wince. “Took a wrong step carrying in some firewood last night. Doctor says it’s bad so I am hoping you can go in for me tomorrow in the Copa de los Nietos at the Polo Club in Curicó. Quite a strong team we’re up against so better get some sleep tonight.”

I felt a mix of sympathy, shock, and adrenalin leaking into my gut on hearing his words. I had brought my stuff, of course, as I had been led to expect some relaxing chukkas at home with my hosts, but… I took another slug of the deep, red Carménère in my goblet. It was really quite good and it soon neutralized the butterflies that had taken flight in my belly.

After sundown dinner was served in the high-ceilinged east wing dining room which featured a long table for twenty, overlooked from above by the ancestral gazes of oil portraits lining the walls. Despite the formal design of the room kittens played footsie with the diners under the table while children ran in and out. It was a bit cool and guests and family alike gathered around an open fire in the patio afterwards. It was a perfectly relaxing interlude after a very long journey.

I did my best to get the sleep that Felix had recommended and it was easy to do in our comfortable beds. The next morning an ample and delicious breakfast was taken late, family style, at the table in the kitchen where Patricia Larson, in addition to being an accomplished painter and sculptor, reigns supreme as the Mistress of Gastronomy at Hacienda San Isidro. It is Patricia who directs and oversees the selection and purchase of all vegetables and fruits from the farm’s gardens and nearby markets, fish and shellfish from the nearby coast, and the preparation of the traditional Chilean fare, such as porotos granados (vegetarian bean soup), pastel de choclo (sweet corn pie), humitas (tamales), cazuela (meat and vegetable stew), and cordero al palo (whole roast lamb—a specialty of the house). As well, Patricia adds her own special touch with seasonings comprising all the flavors, aromas, and colors of her native land.

Indeed it is the owners who take care of the guests here, who are treated like family in the style and tradition of Chilean country life, that they may relax and enjoy their stay as if in their own home.

- - -

The Curicó Polo Club was established circa 1960. Mario Marquez Bisquert has been associated with the club since those long ago days and, along with it, has seen his family grow to the point that he envisioned and sponsored a unique event called “La Copa de los Nietos” (The Grandchildren’s Cup). This year it was a two-day event featuring teams made up from his own ample supply of grand-kids as well as visiting teams. The games were scheduled to begin in mid-afternoon with the kids matches followed by teams in the eight to ten goal range (to one of which I had been seconded) starting at five.

The pleasantly shaded playing field and clubhouse stand beneath a stunning Andean backdrop on the outskirts of the market town of Curicó, about fifteen kilometres from San Isidro. Things were well underway when we arrived with a considerable contingent of members and spectators milling about the clubhouse and the stands.

There was precious little time for a bit of stick-and-ball warm-up. Just mount up, line up, and go. The game erupted in a furious pace which was sustained throughout its six chukkas. Although my injured friend’s warning of the reputed strength of the enemy proved true (we lost 11-6) I was happy to walk away from it without the slightest discomfort or shame. My aim, after all, was to come to South America to play polo with some good guys. Whipping their butts would have been difficult to achieve and more than I deserved. As for the horses I could not have hoped for any better. They unfailingly followed my eye and gave me no reason to think about them, except in afterthought.

The second day proved more interesting, in retrospect, even if I managed to embarrass myself. I knew what to expect after my ice-breaking chukkas of the previous day and was definitely feeling more confident and determined to score. Suddenly I had my chance, forty yards out in front of the enemy goal, I couldn’t miss! I was just about to pop it in when a teammate on my right yelled, “¡Sacalo, Gringo, Sacalo!” My mallet was already heading for the ball but I suddenly thought, ¡Dios mio!, he’s telling me to get it out of there! I must be in front of our own goal! So, I switched to backhand mode and… got it out of there, alright—to the total delight of our enemy who ran off with it in the other direction.

“Gringo, why did you do that?” shouted my frustrated teammate.

“I… I don’t know,” I replied. He shook his head in disgust and rode off.

Ah, how quickly hopes of glory can fade on the field of battle.

We lost 11-6 again, which did not surprise me. But worse yet, I had missed a chance to draw blood, and I could not explain why. But later, in the wee small hours, I awoke from my fitful sleep of regret and suddenly it was clear. I had misunderstood ¡Sácalo! to mean “Get it out of there!” which it could very well do, in the proper context. But only now I realized—much, much too late—that my comrade was referring to an enemy player on my left who he thought was close enough to foil my shot. “Take him out!” was his order, but my incomplete understanding of a language I have studied for fifty years failed me in those critical moments.

Now, that is reason for shame.

But, time heals all wounds, life goes on, and life at Polo San Isidro was pretty darn good. Felix père announced that we would saddle up and ride the historic O’Higgins Trail which crosses the farm and ascends the steep hills to the north offering a fabulous view of the Valley of Curicó and the adjacent Valley of Colchagua as well. The white bearded patrón ordered “Chato” to make it so, which was done with the great skill in all things horse that defines the Chilean huaso, while the rest of us enjoyed a leisurely breakfast on the patio. A departure at the very civilized hour of 10 a.m. soon had us heading off down a dirt road which, after fording a creek of clear, hock-deep water, turned into a trail.

Just before we began the climb we crossed through a very large pasture hard against the hill that was populated with broodmares, foals, and a stallion. These were, of course, the breeding population which produces such excellent polo horses as I had the pleasure of riding on the weekend. Some of these were carrying us now, confident and sure-footed, as we approached the base of the mountain.

The trail began to wind in its ascent as Chato led the way. Machete in hand, he vigorously attacked the vegetation that was attempting to block our way. I was wincing as I imagined a horse’s ear falling to the ground but there was no chance of that. Chilean huasos, like their Argentine gaucho counterparts, are masters of the sharpened blade, and can skin a cow as easily as I can boot up my laptop.

As our altitude increased the view broadened into an enormous vista of central Chile. To the south lay the village of Teno and the larger town of Curicó. To the north the Town of Santa Cruz came into view. Reaching the top a 360º panorama was dominated by impossibly high Andean peaks to the east and complemented by the slightly hazy and cooler air coming in from the Pacific, to the west.

We dismounted and tethered our mounts in the shade of some trees while Chato opened the panniers containing our lunch, prepared by Patricia, and the fermented grape from the wide valleys below. We had worked up an appetite and the food and drink really hit the spot. The sun was high and warm. I imagined Bernardo O’Higgins and company taking in this same view on the occasion of their historical crossing, meditating on their destiny with the fate of a country in the balance.

We all felt wonderfully relaxed and the conversation flowed like the wine. Felix is an avid history buff and always has a story to tell about something that happened last year or two centuries ago. Chato explained the idiosyncrasies of Chilean saddlery. Fellow adventurer “Guy” held forth on his passion for the truffles of his native France, certain that they could be induced to grow here.

Our descent back into the Teno Valley was as exciting as our climb. At one point we flushed out a flock of feral goats, shy as deer. Unlike North America there are few large animals in the wild here. The llama, the alpaca, and the vicuña may be seen in the Cordillera, and occasionally a mountain lion. No poisonous snakes either, I was pleased to know. The Boldo tree (Peumus Boldus) was very common. Used for an herbal tea and as a cooking spice, its leaves can also serve as a natural toothbrush with very effective whitening power.

After seeing the Cordillera from that hilltop we decided to have a closer look. With Felix Senior as our guide we boarded our rental car the following day and followed the Teno River into the high country. After several hours of narrowing road, thinning air, and increasingly spectacular landscape we reached the isolated Vergara Pass on the Argentine border where smugglers have long prospered in spite of a permanent patrol station of mounted Carabineros. The Teno River is born here on the slopes of the Planchon–Peteroa volcano which last erupted in 1937. Steam can be seen rising from its small crater lake.

We dipped our feet in hot pools as we rested in the rapidly growing twilight. Felix told us stories of how San Martin and O’Higgins had, at great cost, led their armies of independence through the rugged Andes for three weeks to engage royalist forces in the West, ultimately defeating them.

As we were returning to the lowlands through the steep defiles, a thin crescent moon became visible as it closely followed the sun toward the horizon. A crystal sliver of ice, it looked different somehow. Then I realized it was reversed from the way we see it in the North. The same phase of the moon is visible from both hemispheres but the orientation is inverted relative to each. This means that the moon appears to wax from its right limb when viewed from the Northern Hemisphere and from the left when viewed from the Southern.

.jpg)

A less expensive way to comprehend this phenomenon for us Northerners would be to simply observe the crescent moon while standing on our heads. But then we would not experience the Bustamante Cup polo weekend—which was suddenly upon us...

- - -

Six teams (including youth and kids matches) were to meet and vie for the Bustamante Prizes, with players from Chile, Argentina, Uruguay—and now, Canada. “Are you ready?” asked Felix as he hobbled into the kitchen—and before I could offer an affirmative nod, he added, “Forgot to tell you… need you to umpire at ten.” That meant I had to gulp and run as it was already past nine. Not far to go, however, with the playing fields just next to the hacienda…

My partner in the law enforcement business was Andrés Mujica, a member of the team I would confront later and in Sunday’s final. We chatted about his recent visit to my hometown of Victoria, B.C., and then we did our job, which happily produced only minimal griping from the players.

Immediately following that it was time to don our colors and play. I was encouraged to see Fernando Azócar y Eduardo Avilés, two of the players of last weekend’s victorious rollover, on our side this time, along with Rafael Garrido and myself. We were facing Rodolfo Busquet, Marcelo Conde (two pros from Argentina), Andrés Mujica, and Samuel Rodriguez.

The weather was perfect—as it had been for my entire month in South America. The crowd was considerably smaller than the previous weekend at the Curicó club. It was a private affair: the Garridos, the Bustamantes, hotel guests, and various invited friends of both families. Fieldside, arriving guests greeted each other and chatted, kids played tag among the trees, while a photographer from Chile’s National newspaper, el Mercurio, snapped away. A sumptuous asado would follow the Saturday game. Just as well I did not know beforehand how good that feast was to be or I would have been thinking of nothing else.

This time there would be no linguistic misunderstandings, I vowed, and I was determined to make some goals as well. As I mounted up I realized I had mislaid my whip. Chato came to my rescue. Whipping out his knife he fashioned a willow branch into a suitable fusta in seconds, and I was off to the lineup, where we had been given one-half goal on handicap.

The throw-in was explosive once again and the crowd responded enthusiastically. We held our own throughout the match, giving and receiving blows. A few players bit the dust—as some had done the previous weekend—but no injuries worth remembering. I was unable to score, but I impeded our opponents in some cases, and generally stayed out of trouble. Once again the San Isidro horses were superb. At the end of it all the difference was still half a goal and the spectators were happy. Tomorrow we would settle it once and for all, but now we retired to the hacienda to prepare for the feast.

As I traveled from Argentina to Chile my Argentine hosts had warned me that the meat in Chile was not all that great. “The fish is pretty good, though,” they allowed. And the fish was good—but the meat was, too. Fantastic, really. Lamb and chicken were prepared in the traditional style—somewhat gruesome to look at in the flickering light of the fire—but the delicious aromas totally conquered the senses and seduced the appetite. And with the eating it only got better. The Bustamantes had brought a few cases of their own special reserve to add to the selection of wines and champagne. Live music, lively conversation, and laughter sparkled in the north patio as Dionysus, Demeter, and the Muses all danced under the stars.

I forced myself to get to bed reasonably early, though, as I was still haunted by the memory of last weekend’s screw-up and I wanted to keep my geezer-ificating brain cells as sharp as I could. The Sunday games would start and end earlier—happily, to allow for another afternoon feast in this same patio before the guests hit the road for home.

In no time I was mounting up again for the final, my lucky willow whip in hand. At least I hoped it would be lucky, and it was, as this whole polo adventure had not cost me so much as a broken fingernail, so far. I did not achieve my wished for goals, however, and I consoled myself with the notion that the story of “¡Sacalo, Gringo, Sacalo!” would actually be a more memorable keepsake than a faded scoresheet with a checkmark after my name (but I admit my ego would have preferred the latter outcome!).

In any case we held the line as well as the day before with another nearly equal clash of forces under the noonday sun, all to the sincere delight of the guests, and ending up with that same half-goal difference in favor of the visitors from the East. But, I was not to leave empty handed. Foreign players received a special prize (nifty polo goggles!) and all received Polo San Isidro jerseys. The ceremony honoring the troops included a special prize, an engraved sterling silver platter, for Chato, commemorating his thirty years of service as chief huaso at Hacienda San Isidro, which nearly bowled him over with surprise.

Tired players and satisfied guests then made their way across the parkland lawns in the dreamy afternoon summer sun to the hacienda patio once again, where a seafood extravaganza called Curanto, a traditional Chilean method of cooking seafood and meat, awaited them. Under the personal direction of victorious player Samuel Rodríguez, the production resembled a ménage à trois choses: a clambake, a bouillabaisse, and a paella valenciana. Seafood, sausages, chicken, pork and vegetables are layered in a large pot with each layer covered with rhubarb-like nalca leaves to seal in the steam. The flavors of the seafood and meat blend together creating a subtle woodsy flavor. Children gathered around the cauldron to see the remarkable variety of sea creatures emerging from it, and drink the delicious broth.

Jugs of exquisitely fresh melon juice were disappearing down thirsty throats as fast as they could be carried from the kitchen. After the exciting afternoon of polo it was a scene of total enjoyment and satisfaction.

On the way back to that last feast I stashed my lucky willow whip in the trunk of an ancient Ford sedan parked in a vine-covered corner of the Hacienda San Isidro. I hope to find it there again someday if I’m fortunate enough to return. It had been a long-delayed but great introduction to South America, and we did not really want to leave. But, on the following day we drove our dust-caked rental car back to busy Santiago and made final preparations to depart, back to far Canada, where the same moon shines just as brightly. Whether or not it is upside down is just a matter of opinion.

- - -

I expect I’ll miss Chile. It will be tough. Yes, it will. But I can take it. Hell, I can do that standing on my head.

Hasta la proxima vez, America del Sur….

(This piece was originally published in POLO PLAYERS'S EDITION magazine, September 2013 issue.)