I, Monkey

or

The Argentine and Me

(by Dan Harvey Pedrick)

-I-

I, Monkey

or

The Argentine and Me

(by Dan Harvey Pedrick)

-I-

Hired by clubs and teams around the world as players of the game try to unlock their deep store of knowledge, Argentine professionals are ubiquitous in polo. They are consummately skillful, daring, cavalier and self-confident to a fault--and often irritatingly outspoken. They are always well mounted because they will simply not ride horses they consider unworthy of themselves. But above all, they are graceful players, creators of the most widely imitated style, and setting the standard against which all other players judge one another.

That much I knew—but I was about to learn a lot more.

I was brimming with anticipation when I rode out for my first one-to-one session with the young four-goal native of el Luján our club had hired for the season to coach and instruct us and to umpire our games. Standing alone on the stick-and-ball field he ordered me to canter slowly around him while working the ball in both directions.

"My specialty," I said to myself as I eagerly did as he asked. We'll probably move on to a more advanced topic when he sees how well I can do this, I thought. After a few minutes I looked up from my intense concentration to establish eye contact with el Maestro. But to my dismay his face was buried in his hands. I turned back the other way. He must have a headache, I mused. It's a long flight from Buenos Aires to Victoria, after all. I looked up again. This time he was shaking his head, laughing. What's the matter with this guy, I wondered. Finally I stopped. "OK, Maestro, what the hell is so funny?" I demanded to know.

"You, Maestro" he replied (our conversations regularly oscillated between English and Spanish—I called him 'Maestro' because of his skill; he called me 'Maestro' because of my age). "You look like a monkey."

"A... monkey?" I replied with deepening shock and incredulity. Eighteen years of polo and I look like a monkey. I was at a loss for words and awash in dejection.

"Yeah, a monkey. A mad monkey. You're all bent over, uptight. And when you hit the ball you look like you're in pain." He did this imitation of me hitting, grimacing and growling like a beast as he swung his arm. Sure enough it reminded me of the winged monkeys in The Wizard of Oz. But did it look like me? I hoped not.

"Look," he said, "you've got to open up your body, lean out and over the ball. Show it your breasts. Arch your back. Stick your butt out."

Show it your breasts? I couldn't believe I was hearing this.

"I am sorry," he went on, "but you must try to look like a… a… a homosexual."

With that I dropped my mallet and, gasping with frustration, just about fell off my horse as well. "Now hold on a moment, Maestro," I spluttered, "you can't say that here. This is Canada!" Suddenly an attractive young female groom went stick-and-balling by and both our heads turned.

"See, Maestro," he said, "I want you to look like that." She was looking good, I must say, and doing all those things he said that sounded so preposterous when I thought of them applied to my angular frame: her back was arched, and, well, you know, all the rest of it. But she's a she, dammit, and I'm a he!

"Like a girl, then?" I said. "You want me to look like a girl, is that it?" He shrugged in that Argentine way, as if to say, 'Well, whatever.' I went on struggling, trying to get my head around such a radical concept. "So, you want me to… get in touch with my… my inner girl?" I replied sardonically.

"Yeah, that's it, your inner girl. Find your inner girl and bring it out. But first you have to find your inner monkey—and kill it!" He signalled that today's lesson was over and I rode slowly back to the barn.

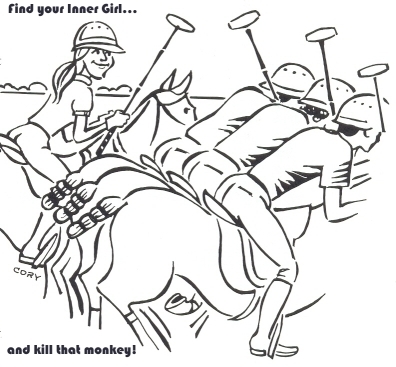

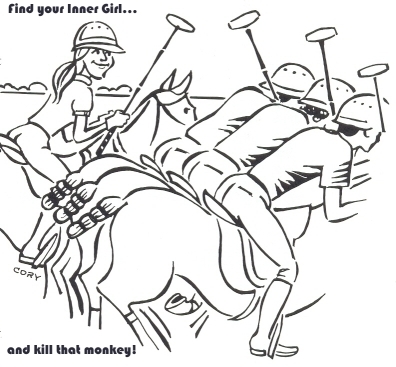

Later, we sipped mate in the clubhouse and looked through some back issues of POLO. "There," he said, handing me an open, worn copy from past years. "There's your inner girl—and there's your monkey." The illustration showed a girl playing polo with three guys. Sure enough, although only a cartoon character, her posture was as keen as a cocked bow while that of her companions was totally ape-like: backs hunched and shoulders drooping like a trio of slavering orangutans.

It may have been the stimulating effect of the mate, I don't know, but suddenly I started to feel an insight coming on. The key is the Spanish word "gracia," a term that can mean much more than simple physical grace. Rather, it is the psycho-physical quality that the best matador must have, that which allows him to pace slowly and calmly in front of a raging bull, facing implacable Death with nerves of steel, stepping cat-like, one foot directly in front of the other. But while the corrida de toros is a very masculine world, the torero takes on a female role therein: he prances about like a ballet dancer in a shiny, tight-fitting costume; he poses like a statuesque woman in high heels, back arched, breast and butt protruding, in fearless mockery of the extreme danger; he teases and seduces the bull, touching the phallic horn—all typically female behavior.

In Hispanic culture, often regarded as excessively "macho" by others, this is the moment when the bravest of the brave can cross the line of their masculinity and venture into Plato's androgynous world of shifting gender roles with impunity, encountering his Jungian anima, searching for his other half in hopes of becoming whole again. In short, he gets in touch with his 'inner girl'—and thereby exudes gracia.

I shared these thoughts with my mentor and he seemed to agree. "But as the matador kills the bull," he said, 'you must kill the monkey. That's going to be the hard part," he said as he passed me the mate gourd. "You've got a monkey inside of you as big as King Kong."

(to be continued…)

I have met the enemy—and it is me. Knocked off my high horse, so to speak, I tried to salvage some remnant of my self confidence as I struggled to adopt new techniques of riding and hitting—to say nothing of finding that inner girl that el Maestro talked about. "You must keep your body quiet," el Maestro said as I rode around him at the canter while standing in the stirrups. Your legs below the knee should be still, your body straight and right above the pony's center of balance. Don't pull on the reins to keep yourself up! Point your toes down, that'll help you grip with your thighs. Stop!" He walked over to me and grabbed the head of my mallet. My thighs naturally tightened as he yanked on it as if to pull me out of the saddle. "Feel that?" he said. "Keep gripping with your thighs like that all the time, hard! You have to stay armado, Maestro, with your mallet directly in front of your breastbone, at twelve o'clock, not bouncing and flopping around. Understand?"

I was familiar with some of these points having studied them with RL years before. But I guess I got lazy and didn't realize how, like those insidious alien pods in The Invasion of the Body Snatchers, the "monkey" was slowly taking over my game. Now it seemed I had to learn everything all over again. But how long would it take? I didn't need a calculator to tell me that I was in the autumn of my polo career, such as it was, and I thought I could sense the qualities of sharpness and flexibility, both mental and physical, beginning to fade. As for my inner girl—perhaps my inner crone by now—it must be somewhere deep inside my psyche, buried under countless layers of conditioned responses and old habits I had become comfortable with over the years. But el Maestro seemed to be suggesting that it could still be summoned through the appropriate physical and mental exercise. "Athena! Arise!" I chanted to myself—but no one answered.

The first group lesson from el Maestro was a significant departure from the easygoing play our club was accustomed to. He addressed all of the players (who presumably had inner monkeys to deal with also): "The first thing we are going to do is slow down," he announced. "You will play chukkas at a slow canter. If you slip into a gallop I will blow the whistle and we will start over. Bonzo [not his real name], where's your whip?"

"I don't use a whip," replied Bonzo.

"Why not?" countered el Maestro, "This is polo. You use a whip in polo. Go get one."

"Chi-Chi [not her real name], where's your breastplate?"

"I don't have one," replied Chi-Chi.

"Go get one," ordered el Maestro, "If your saddle doesn't stay up on your horse's withers how can you hit the ball properly? This is polo."

"Spanky [not his real name], you're on the wrong lead. Do you know how to change leads?"

"I think so," said Spanky.

"Slow down, into a trot if necessary, shorten the opposite rein a bit and lift your pony's shoulder. Feel the rhythm of it. This is where you need your whip. Is something funny, Maestro?"

"No, Maestro," I replied.

"Then quit smiling. This is serious. This is polo!"

The slow-motion chukkas continued for weeks under a blistering summer sun and the watchful eye of el Maestro. As the preceding sample of dialogue indicates, his criticism was blunt and his praise was scant. Occasionally he would mutter something like, "By the end of this season I hope to see you doing something that looks like polo." While one-on-one sessions focused on riding and hitting, group sessions focused on defense strategy and team play. As each instructional point was made, he made certain that every student understood fully all of its implications. No Polo Player Left Behind. Occasionally he'd set us up by saying something like, "You've all been told since you started playing polo to take the man first, then the ball. Right?"

"Right!" we all answered in unison.

"So why don't you do it then?"

Groans.

"Taking the man means taking the man, not just riding along behind him and waiting for him to screw up so you can get the ball. If one person on a team doesn't do this the whole damn thing falls apart. Right, Maestro?"

"Yeah, Maestro, that's right," I replied, knowing that something unpleasant was coming my way.

"So you've got to stop staring at the ball all the time like a border collie on steroids and start concentrating on the man. Understand?"

"Sí, Maestro."

"And another thing… you're all too friendly out here. 'Where do you want to play?' 'Oh, I don't know, where do you want to play?' 'Oh sorry, excuse me.' 'Well played.'--C'mon, guys, you Canadians are too polite. Organize your team. Talk to each other. Get mad a little bit. This is serious. This is polo!"

For me el Maestro's criticism did not end when we left the field. I had become his farrier as well as his student and even when I was bent low under one of his horses I had to listen to things like: "Maestro, you've got to stop hitting the ball too hard. You act like you hate the ball. That's one reason why you break your mallets. Next time we go out there I'm going to show you how to kiss that ball."

'Ride like a girl, kiss the ball... Why don't you kiss my butt,' I wanted to say. This whole monkey business thing was becoming a torture.

And by now the mounted monkey of my subconscious self had begun to haunt my dreams as well as my waking hours. In one dream I revisited a traveling circus I once witnessed in rural Mexico. The tatterdemalion ringmaster placed a monkey on a pony where its hands and feet were made fast to the saddle with straps. The pony was then lunged over hurdles to the delight of the crowd as its unfortunate rider, clearly bereft of any equestrian desire or ability whatsoever, bounced around on its back, screaming in agony and terror. Only a dream--but so real! Waking in a sweat from my fitful sleep I swear I could smell the pungent odor of circus animals and, worse yet, taste the sickly sweet residue of fresh bananas.

(to be continued…)

As I continued the search for my inner girl to replace my inner monkey I had to admire el Maestro's priestly devotion to his sport. And like every good priest he had a cosmology, a theology, and a canon law that he never wavered from. Its basic creed was simple: good polo good, monkey polo bad. But, as God is in the details, he had a reason for every rule, reasons that he made certain were understood by all, e.g., the saddle must be set well up on the withers (to place the rider as close as possible to the pony's center of balance); tails should be taped after being tied (to eliminate the possibility of unraveling and spoiling a shot); polo ponies should be shod every twenty-eight days (to reduce strain on ligaments and the risk of pulling a shoe). As a farrier I liked that last one but there were many more in his daily catechism which, in the interest of brevity, I will omit.

Neither was the importance of the playing fields overlooked in his litany of what should be a primary concern to every polo player. He lowered the blades on our mowers and cut the turf with careful attention before every scrimmage and game. "It will not be necessary to play a man for a miss if the ball sits up and is not buried in the grass," he said. He mustered us on the field on days when we did not play and armed us with bags of sand and small garden trowels. As we fanned out in a line across a desert of divots and dead spots he ordered us to drop to our hands and knees. "Now, scratch the thatch and dead grass out first," he explained, then fill the hole with the sand and level it. This will keep the ball rolling straight and true. This will improve everyone's polo."

I must admit, the tedium endured in these group work bees produced a memorable feeling of camaraderie as well as the results el Maestro promised: everyone hit better and the ball traveled farther. But I grappled with the monkey still.

Another one-on-one session with el Maestro: "Maestro, just before you hit the ball you are way too tense. I want you to relax your body but remain mentally focused on what you are about to do. Look, there are three things you must do when you hit the ball full swing: first, as you approach the ball, swing the mallet slowly from your forearm keeping your elbow close to your ribs; when the mallet is going down, brake it a little bit, feel its weight, and tighten your grip. Use this movement to get your timing right for the big swing. Two, Adjust the speed of your horse. Now for the big swing. Get up in the stirrups. You want to strike the ball when it is just in front of your foot. Turn your upper body so that your breastbone is parallel to the line of the ball. Lean over and reach down--don't hunch!--and snap your wrist as you hit the ball with an upward blow.

"Three, you must now follow through. Follow the ball with your eye, your arm, and your shoulder. Let the energy of your swing flow out after that ball. Absorb the remaining force by swinging the mallet around one more time with your wrist as you return to the saddle and your mallet returns to the starting position at twelve o'clock. You must do all this smoothly without jerking your pony's mouth or letting your legs flop around like a pair of rags. That's how you hit the ball hard, Maestro--but smoothly, quietly, keeping the monkey always in his cage. Got that?"

"Oh sure, got it, yeah, Maestro, no problem." But there was a problem. Namely, I couldn't do it very well--not just yet anyway.

"To hit the ball short is even more difficult," he went on. You've got to get way up, lean out over the ball. You must use your wrist a lot here. Tap it lightly at a dead slow canter. No, no, that's way too hard! I don't want to see it go two meters, I want to see it go two feet--or less. Now try the near side. Change lead! Tap, tap--not so hard! You've got to build up more strength in that wrist, Maestro."

It certainly made beautiful sense the way el Maestro described it but by this time the recurring image of the monkey was becoming a source of ever deeper anxiety for me. I could barely manage to control it while practicing but in the excitement of actual play it was even harder. Scrimmaging at close quarters it was most likely to appear in the form of gnashing teeth, slashing mallets, and bitter oaths. At that point the ideal picture of polo poetry in motion described by el Maestro descended into a state of animalistic anarchy, brawling baboons on horseback, a cacophony of simian shrieks and screams. And it seemed even worse now that it had been called to my attention.

The enormity of the problem was really starting to get to me and my self image as a cool guy who played a half decent game of polo was history. I was both terrified and depressed as I confronted this aspect of myself that I simply hadn't faced before; terrified because I honestly was not at all sure that I could conquer it, and depressed because all the fun of polo had suddenly been taken away from me. El Maestro wouldn't let me ride and hit the way I had before so all I could do was ride around and get yelled at. I began to consider cutting and running but it was too late. As I squirmed under the merciless gaze of the Banana-eating Beast Within (as well as that of el Maestro) I offered all sorts of excuses to rationalize my failure and justify my retreat: "My horses are no good. My mallets are no good. I'm too damned old to learn anything--and I never could afford to play this game properly anyway!"

El Maestro was well aware of how hard I was taking it, but he acted like he'd heard it all before. "'stá dura la mano, Maestro" he said, handing me the mate gourd (which roughly translated means, life is hard then you die). "So, let's have an asado."

And that was his standard cure for everything: get buzzed on mate and eat a great whack of meat. He immodestly allowed that he was in the high-goal range as an asador and readily demonstrated his knowledge of the parilla (the barbecue pit) with such culinary delights as matambre (always on the verge of becoming tough if you are not careful), churrasco (thin, boneless beefsteak), and chimichurri (a spicy purée/vinaigrette). And I must admit it was effective, for a while anyway. But after the charcoal embers died down and the last of the wine was poured I was still face-to-face with that personal monkey, grinning, shrieking, bouncing up and down--and it was driving me insane. I had to think of a way to sneak into the foul creature's lair and throttle it with my own hands. But really it came down to this: was I to be a Monkey-man or a Girlie-man? It pretty well had to be one or the other according to el Maestro. With apologies to The Terminator I decided to choose the latter--if only because monkeys can't vote.

(to be continued…)

El Maestro's approach to polo was holistic; he considered each and every aspect of the game to be as important as any other, all contributing to one integral unity. "You need many things to play polo," he said.

It's true. You need many things to play polo, some tangible, some intangible. You need some good horses. You need a ball, and a ground, and some other people to play with. You need a strong desire to play and the motivation and the means to make the commitment to continue playing. But most of all you need that stick--or a taco as the Argentines call it. Complaining about breaking mine all too often finally caused el Maestro to have a look in my mallet bag.

"OK, let's see your best one," he said. I pulled out a scarcely used 53 that came from one of the best makers in the business and handed it to him. He stepped forward on his right foot and pressed the handle into the front of his thigh. He began to vibrate it to the point that it looked like a plucked guitar string. Then he suddenly tossed it into a nearby garbage can. "A fishing pole," he said derisively.

"What the hell's the matter with it?" I exclaimed. "¡Caray! Is there anything you like about me, Maestro?" I blurted out in frustration.

"Yeah, you have a nice daughter," he replied, "but your mallet is a dud. Look where it breaks," he went on, taking the mallet back and vibrating it again while ignoring my exasperation. "Way too far up the cane. You want it to break right here just below the halfway point," he said as he took one of his own and demonstrated.

"But that's the same brand as mine," I said. "How come mine is a 'fishing pole'?"

"Listen," he said, "when mallet makers get a fresh load of cane, all the good stuff is snapped up right away by the high goalers. The rest…"

"Ends up with dopes like me," I replied cynically.

He just shrugged, non-commitally. "Look, Maestro, tell you what. I'll sell you a good one from my bag. Then you'll know you have at least one good mallet."

I agreed to buy one of his just so we'd have one thing we could agree on, one constant factor--and eliminate one of my excuses for failing to find my inner girlie-man. The next day I tried it in a game. It hit better, for sure. At least it did until I accidentally swung it against the toe of an opponent's pony, at which point the head broke off as neatly as if it had been power-sawed.

"¡Mala leche!" shouted el Maestro. But he had proved his point about the mallets so I just traded it in for a couple more and kept going. But before I took delivery of them he carefully wrapped a strip of bicycle innertube material around the white tape on the lower part of the canes. "This will help, but you must learn to avoid hitting the ball with the cane rather than the head," he said . "That, and hooking too hard is why you're breaking your mallets."

One evening el Maestro and I had our last real mano-a-mano discussion about the monkey. "Everybody's got one, Maestro," he said.

"Even you, Maestro?" I asked, grinning like a chimp.

He just shrugged and continued: "Having one is not the sin," he said, "but failing to control it is. Look, don't stick-and-ball so much before you play, now," he said, "just sit down and meditate, settle your brains, find clarity. Visualize your inner girl putting the monkey in his cage and locking the door. Focus on what you are going to do. When the monkey's rattling the bars of his cage, that's when you've really got to stay cool," he said.

"You know," he went on, "other sports are very different from polo. They are not so complex. In rugby or boxing or American football, for example, you can increase the level of violence and maybe win as a result. In polo, with the ever-present possibility of a collision or fall at high speed, the potential for violence is always there, for everyone. You can't increase it without increasing the risk to yourself. You have to stay cool and collected in order to win. So, allow your opponent to let his monkey out of the cage while you keep yours under your control. You control the game by controlling your mind. Control, control, control!"

The summer had been a constant challenge but I noticed el Maestro was starting to lighten up on us now, even giving the odd bit of encouragement in the form of a cautious word of approval. So, I kept at it--trying to forget what I thought I knew and attempting to absorb and internalize the doctrines of my young mentor from the other end of the world--but it was terribly slow going and I feared I had become a far less effective player than when the monkey had run free. But, we were paying this guy to tell us what to do based on the belief that we would rise to a higher level at a rate directly proportionate to the frequency of the experience. So, I clung to the idea that if I kept the faith eventually I would progress beyond what I had accomplished before. But when would it happen? It may be just a matter of time--but did I have enough of it? If only I had met this guy years earlier, I thought. It's not just that damned monkey, I suddenly realized, it's Time, relentless and implacable Time.

Still, it felt like something had changed. I had modified my posture, for one thing, and somehow that seemed to be changing my attitude, too. For example, I was more conscious of the way I looked now, on a horse anyway. Riding past the the clubhouse I found myself giving a sidelong glance at my reflection in the plate glass windows. I began to notice a chronic ache in my thighs. I started paying attention to TV commercials about spot remover (and then squirting some on my whites before tossing them in the washing machine). And I wondered wistfully: would I ever look… pretty?

Did these disturbing thoughts mean I was finally finding my Inner Girl, about to get some real gracia at long last? I cautiously decided that…it might--but I resolved to quit looking immediately if I felt the slightest desire to cry and then go shopping for clothes to cheer myself up.

If el Maestro had any worries of his own, they were rooted in his doubts about the legacy he would leave behind. "I feel I have struck a hard blow against the monkeys here," he said in a reflective mood, "and driven them back into the jungle where they belong. But what's going to happen after I leave, Maestro?"

The next day he was gone. I don't know if he fully understood or appreciated us B.C. Coasters, our quirky sense of humor and our laid back approach to polo, and to life. I hope he did. It had definitely been a clash of cultures with polo as its nexus.

In spite of almost two decades of involvement with polo this was my first sustained encounter with the Argentine mentality. The Argentine player seems to understand polo instinctively and at a very deep level, a logical result, I suppose, of growing up in a country where the game is part and parcel of the family and social activities of the landed gentry. Argentine boys who are fortunate enough to be born into this world find themselves playing the good old ponies that their fathers played by the age of five, and their abilities grow naturally and with great vigor from this experience. It is hard to imagine that there must have been a time when the Argentine did not have his impressive knowledge and superior skill in polo. I think it is reasonable to add that he can also be arrogant, opinionated, and intolerant of anything that he considers heresy.

In addition to this kind of background el Maestro had personal qualities that would set him apart in any group. One, he ignored our local hierarchy and criticized any and all who deserved it regardless of their status in our club. Two, while he often reminded his students that polo was a very difficult subject, he always made it clear that dropping the course was not a topic for discussion. Three, he did not fail to make certain that his students understood what he was getting at before moving on to the next lesson, even if the others had to stand by and wait for the slower ones to catch up. As someone who managed to exasperate every teacher I ever had from kindergarten on--some to the point of practically giving up in despair--I appreciated that a lot. Finally, his reference to the inner girl and the monkey was a brilliant and vivid analogy. I may never improve my game to the level that he tried to inspire us to do, but I will never forget those images.

I gazed out across our playing field and listened carefully for the chattering of monkeys but it was eerily quiet. "Well, I'll miss him," I said to myself, dabbing at my eye with my sleeve. "No polo today... maybe I'll go to the mall and see if there are any sales on…"

A special thanks to Maximiliano Marina of Luján, Argentina, who played the role of "El Maestro" to perfection.

(Photo by Robin Duncan).

The Author (in a rare moment of clarity!).

(Photo by Tony Austin).

Back to Victoria Polo Club Home Page