Dante's Divine Comedy --

The Apotheosis of a Literary Genre

by

Daniel Harvey Pedrick, B.A.

for

Italian 570

Dr. Lloyd Howard, Prof.

1. Introduction

Dante's Divine Comedy --

The Apotheosis of a Literary Genre

by

Daniel Harvey Pedrick, B.A.

for

Italian 570

Dr. Lloyd Howard, Prof.

1. Introduction

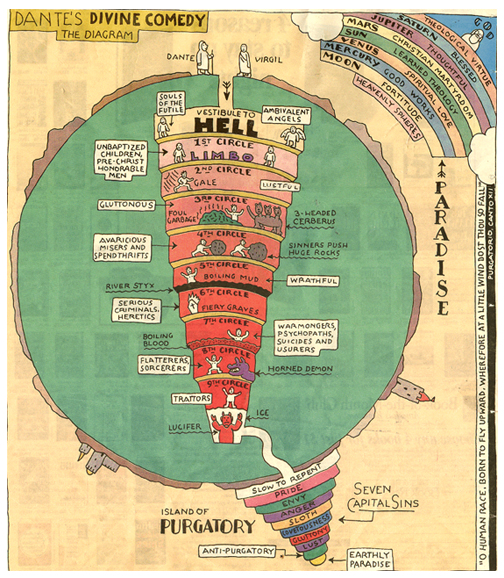

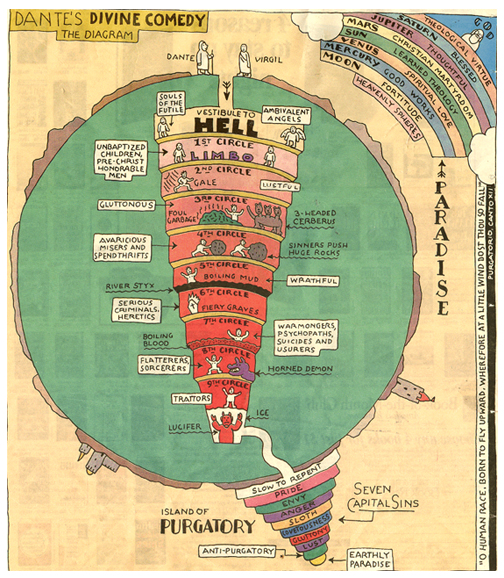

The journey to Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven in Dante's Divine Comedy

represents a period pièce-de-resistance of a literary genre of otherworld

journey/vision literature that has fascinated humankind throughout the ages.

The idea of travel and communication between the world of the living and the

world of the dead appears in the Old Testament as well as the New. The theme

also afforded subjects for such creative geniuses of classical antiquity as Homer,

Plato, Virgil, and a number of anonymous writers of lesser talent perhaps but

whose stories have also survived.

Otherworld journey/vision literature appealed strongly to early Christian

writers, keen as they were to establish a new vision of the universe in the minds

of converts. This genre also enjoyed a great popularity in medieval Europe

where a considerable number of accounts and narratives were published during

the Middle Ages.(1)

In general the medieval examples of vision literature share a great deal of

common material and ideas, inspired as they are by Christian cosmology and

theology. Most of these are narratives that describe individual journeys to or

visions of the world beyond mortal existence. They stress the Christian belief

that the soul is separated from the body at death, judged according to its moral

behavior on earth, and allocated a place appropriate to await the Last Judgement

at which time it will be assigned its final place for eternity.

It is very likely that Dante was familiar with this literary genre and drew upon it as

he did other works--contemporary, early Christian, and of classical antiquity--to

create his brilliant rendering of the Christian otherworld in the Divine Comedy, a work

that, owing to the author's great imagination, ability, and talent, far surpassed all

previous efforts in this direction.(2)

This paper will seek to point out some areas where Dante found inspiration for his

Divine Comedy in two earlier literary works that he knew well (The two other works

are Virgil's Aeneid - Book VI, and The Vision of St. Paul, also known as The

Apocalypse of Paul, author unknown).(3) As the literary acclaim of Dante's Divine

Comedy (both in the writer's own epoch as well as in later times) began with the

immediate popular success of Inferno, this paper will also examine the history of the

psychological concept of hell in an attempt to shed some light on the durable appeal

of this often gruesome but ever popular subject.

2. The Concept of Hell

It is interesting to note that among the otherworld journey narratives the

destination of hell seems to have held the greater interest for readers as Dante himself

discovered with the early publishing success of Inferno. In this first book of the

trilogy that comprises his Divine Comedy, Dante arguably develops and elucidates the

notion of hell more thoroughly than any writer before or since. Setting the fact of

Dante's singular literary skill aside for the moment, one is obliged to wonder if this

macabre fascination with hell exists because the human mind has a natural tendency

to focus its interest on the diabolical. Or, could it be simply that the infernal is easier

to try to describe than the celestial? Eileen Gardner opines in her Medieval Visions of

Heaven and Hell:

Hell is clearly imagined and described over and over. Often the

details are the same--fire, bridges, burning lakes, horrid little

creatures pulling out sinners' entrails. They are physical, colorful,

vivid images... By contrast, heaven is a pale place, basically

without any reality... If we attempt to articulate a modern

understanding of the nature of the heavenly, it would probably best

be described as unity--psychic, physical, spiritual. But a

description of heaven or unity is again limited by language. The

very nature of words is much better suited to hell--heaven is best

revealed or described not in words but perhaps in a mandala--some

visual unity. This is extremely difficult to elaborate verbally. The

feeling of unity and wholeness is much more profoundly difficult to

describe than diversity since language is fudamentally rich in that it

is diverse, and unity is ineffable.(4)

While attempting to comment on the relative appeal to readers of heaven and hell,

Hypatia Bradlaugh Bonner seems to speak for those who may have read Dante in a

superficial way but on whom the more complex levels of meaning in the work may

have been lost:

For one who has read Dante's Paradiso and Milton's Paradise Regained,

there are hundreds who are more or less familiar with the Inferno and the

Paradise Lost. Tales of bliss quickly cloy the imagination; there are very

few who are not soon weary of descriptions of unrelieved joy.(5)

Whatever the reason for hell's apparent enduring fascination among readers past and present, I shall continue with a brief discussion of some early concepts of hell which plainly contributed to the one finally adopted by Christian theology and refined by Dante himself in Inferno.

The notion of the other world beyond life as a place of moral retribution has

origins that far predate the medieval mindset of Dante and his contemporaries. These

origins extend into the remote past and thence formed the basis upon which the later

Judeo-Christian ideas of Dante regarding the architecture of hell were built.

The Vedic poets of ancient India recorded their concepts of an other-wordly abyss

and asked their gods to send the deceased souls of the wicked there:

Indra and Soma, plunge the wicked in the depth,

yea, cast them into darkness that hath no support...

So that not one of them may ever thence return ...

Protect us, God,; let not the wolf destroy us(6)

Bloomfield is less apologetic on the subject of the Rg Vedic hell:

The [Buddhist] prospect of paradise is marred to some

extent by visions of hell, the inevitable analogical

opposite of paradise, that deep place of bottomless, blind

darkness, which in a later time is fitted out with the

usual gruesome stage-setting in the style of Dante's

Inferno, or of the wall-paintings in the Campo Santo at

Pisa.(8)

Later, the notion of moral retribution in the otherworld based on actions and

behavior in life--the law of karma--became more well developed in Indian

religion, as we see in the Upanishads:

Verily, one becomes good by good action, bad by bad action.(9)

meaning that, unlike the theory of Shakespeare's Marc Anthony, the good men do

does live on and determines the quality of existence that their immortal souls enjoy--or conversely, suffer.

In early Buddhisim the laity was instructed by the followers of The Enlightened

One that if they practiced the prescribed moral behavior they would attain sufficient

virtue to be born again into a kind of heaven while those who failed to do so could

expect to wake up--or remain in--hell. This was intended as a simplified and symbolic

way of communicating the tenets of the Buddhist religion to the common people who

were perhaps less able to comprehend the more abstract philosophical doctrines that

preoccupied Buddhist monks. Buddhist monks viewed the journey to Enlightenment

as a process of escaping from the depths of one's own mental hell and climbing to the

heavenly heights of pace and serenity.(10)

Later, as the Buddhist religion was split by the inevitable process of sectarianism,

certain schools began to take such abstract concepts and give them more tangible

form--especially the concept of hell. These included a detailed geography of the

physical world in general and the topography of hell in particular, complete with

graphic and gruesome descriptions of the horrible tortures inflicted on the damned.(11)

Nevertheless it is important to remember that according to all forms of Buddhist

philosophy and doctrine, then as now, the concept of hell is presented more as a

means to induce self-reflection and direct the subject towards the goal of

Enlightenment rather than a threat of punishment.

In early and medieval Christianity the concept of hell was employed for the same

didactic purposes but represented more emphatically as a final physical destination for

the condemned soul who failed to follow the law of God in life. Dante certainly

represented hell in this way in Inferno and many of his readers understood his

spellbinding tale to be the faithful account of an actual physical experience.

The cosmological vision of the ancient Semitic peoples (which provided the basis

for that of Judaism later) consisted of three levels: earth, heaven and the netherworld.

The upper realm was populated by the gods, who granted the lower world, earth, to

humans. An even lower world was populated by a god known as Mot who ruled over

the dead and other infernal dieties in a huge subterranean cave called Sheol. Once in

Sheol, the dead could have no contact with the celestial gods although they still might

communicate with the living through necromancers.(12)

An example of this kind of communication is recounted in the first book of

Samuel. King Saul is desperately trying to divine the outcome of an iminent battle

with the Philistines but his traditional methods for doing so--prayer, prophets, and

dreams--come up with nothing. The King had previously pursued a policy of

supressing wizards and necromancers and driving them underground but now, in

desperation, he ironically calls on one of them for help. A frightened woman with the

requisite skill obediently summons up the prophet Daniel from the underworld at the

behest of her desperate monarch. The soul of Daniel, after complaining bitterly about

being disturbed, informs the King that he will die in battle on the morrow--and of

course he does. (I Samuel 28)

Under the heel of successive dominant foreign governments, the people of the

Israelite states had developed the concept of one god exclusively dedicated to their

protection, perhaps in the desperate hope of finding a saviour to satisfy their often

frustrated national ambitions. As Jewish theology evolved, Sheol became the abode of

only the wicked while the blessed and the righteous could look forward to being

"received" in a more pleasant atmosphere by their one god, Yahweh. This concept is

expressed in Psalms 49:

Like sheep [sinners] are laid in the grave... and the upright

shall have dominion over them...

But God will redeem my soul from the power of the grave:

for He shall receive me.

and another psalmist (Psalms 55) repeats the same theme even more explicitly in his wishes for the iniquitous:

Let death seize upon them, and let them go down quick into

hell...

As for me, I will call upon God; and the Lord shall save me.

These psalmists, however, offered no real descriptions of hell.

The god Mot was eventually all but forgotten but no ruler had taken his place, as far as most Jews were concerned. That would happen by the time the Jewish culture and religion clashed with the Hellenistic during and after the Maccabbean Wars (c.168 B.C.E.).(13) In the aftermath of that conflict, Judaism--for such it could now be called--was rent by sectarianism. Prominent among these competing groups were the Essenes who saw the world as an apocalyptic struggle of cosmic war between the forces of good (the Sons of Light, i.e., themselves) and evil (the Sons of Darkness--or everbody else).(14) Satan, who in earlier Hebrew tradition had been an angel of good standing in God's heavenly court but later became associated with the Fallen Ones, was a natural choice for the job of King of Hell. It remained only for the newly emerging Christian sect to place him on the throne.(15)

As I will show, this apocalyptic vision of the Essenes and other radical Jewish

sects of the fist century--including the early Christians--greatly influenced the later

Vision of St Paul, but first I will discuss the Hellenistic or Greco-Roman conception

of the otherworld, as it was the most well-developed one yet to appear and also had a

profound influence on Jewish and Christian (and Dante's) thought.

The underworld of Hades was, like everything else in the sphere of the gods of

classic mythology, accessible to whomever could make the right connections. Pagan

gods exhibited many personalities and moods and were capable of granting favors to

other gods and to mortals--and were just as capable of changing their minds.

Virgil's Aeneid--Book VI is an early example of the otherworld as a place that is

actually visited by someone who returns to tell the tale. Urged on and guided by Sibyl

(who, like Dante's guide in Inferno, has been there on a previous errand) Aeneas

draws his sword and marches into Hades. There he has a guided tour and an interview

with the shade of his dead father who foretells his son's destiny and the lineage that

will spring from him. Virgil's Aeneid--especially BookVI--was a major source of

inspiration for Dante both in concept and in form. Dante, of course, deliberately and

without apology borrowed much of the landscape and even the dramatis personae

from this epic tale for his Inferno as it would seem he wanted his Comedy to become

part of the literary continuum of epic poetry begun by Homer.

The Christian hell, with its heavy emphasis on punishment, pain, and guilt, owes

much to the authors of the New Testament, principally St. Paul, and to other early

Christian writers like Justin Martyr and John Chrysostom.(16) The written account of

Paul's own purported journey to the otherworld, which first appeared in 388 C.E., also

took some inspiration from classical mythology,(17) and in turn, Dante took some from

it. Dante indicates early in Inferno that he was familiar with the popular

vision/journey of St. Paul:

Later the Chosen Vessel travelled there,

to bring us back assurance of that faith

with which the way to our salvation starts. (Inf. II, 28-30)

Here Dante acknowledges a previous explorer--if not truly of hell, then certainly of

the equally uncharted territory of publishing otherworld journey/vision literature, for

the spurious Pauline narrative was a long-lived popular success. Both works may be

seen as benchmarks of the evolution of the concept of hell in the Christian mind,

indicating how over time the infernal realm had become more a place to be navigated

with care since the relatively mild days of Sheol and Hades. Nevertheless, hell

retained an irresistible fascination for the medieval mind, a fact of which I suggest

Dante was well aware and took full advantage.(18)

3. Common Elements in the Genre of Otherworld Journey/Vision Literature

In looking at The Divine Comedy of Dante as well as the two other selected examples of otherworld journey/vision literature (Virgil's Aeneid - Book VI, and The Apocalypse of Paul, author unknown) we will consider twelve common elements or recurring motifs in this genre according to Gardner(19) that make for interesting points of comparison. As we shall see, these common elements are not necessarily present in each example.

1. One individual visionary/pilgrim/traveller.

Dante/pilgrim is the lone mortal on his trip and enjoys no other flesh-and-blood

company throughout its duration. Only he makes the entire journey, exchanging guides

and mentors as he proceeds. The terrifying fact of his solitude and vulnerability

overwhelms him on several occasions:

And when I saw the ground was dark in front

of me and me alone, afraid that I

had been abandoned, I turned to my side;

and he, my only comfort, as he turned

around, began: "Why must you still mistrust?

Don't you believe that I am with-and guide-you? (Purg., III, 19-24)

Although in Inferno he is under the protection of the first of these guides (the shade

of Virgil) and even under divine sanction, he still believes he faces real danger from a

number of threatening elements.

The color cowardice displayed in me

when I saw that my guide was driven back,

made him more quickly mask his own new pallor. (Inf., IX, 1-3)

"Turn round and keep your eyes shut fast, for should

the Gorgon show herself and you behold her,

never again would you return above," (Inf., IX, 55-57)

I could already feel my hair curl up

from fear, and I looked back attentively,

while saying: "Master, if you don't conceal

yourself and me at once-they terrify me,

those Malebranche; they are after us;

I so imagine them, I hear them now." (Inf., XXIII, 19-24)

Dante/pilgrim may have plenty of company and even divine protection, but his fear is

that of a mortal man facing the terrible loneliness that the immediate threat of personal

extiction inspires.

Writing with the third-person voice of the omniscient narrator, the poet Virgil tells

the story of Aeneas who (accompanied by a guide and mentor, like Dante) descends

into the underworld of Hades with the Sybil, a lone mortal leaving his companions on

the shore of the Cumaean coast to await their leader's return.

These rites perform'd, the prince, without delay,

Hastes to the nether world his destin'd way. (Aeneid, VI, 336-337)

The Pauline journey, in contrast, makes it clear with its strong first-person voice(20)

that the principal character is also a lone mortal (my italics):

While I was alive I was caught up in my body to the third heaven.(21)

2. Soul is separated from the body.

Dante/pilgrim is a living, breathing, conscious mortal--not a spirit. This fact makes

him very conspicuous to all in the netherworld and causes many a shade to wonder in

amazement:

"O living being, gracious and benign,

who through the darkened air have come to visit

our souls that stained the world with blood, if He

who rules the universe were friend to us

then we should pray to Him to give you peace

for you have pitied our atrocious state. (Inf. V, 88-93)

and,

When they became aware that I allowed

no path for rays of light to cross my body,

they changed their song into a long, hoarse "Oh!"

And two of them, serving as messengers,

hurried to meet us, and those two inquired:

"Please tell us something more of what you are." (Purg., V, 25-30)

and

And you approaching there, you living soul,

keep well away from these-they are the dead."

But when he saw I made no move to go,

he said: "Another way and other harbors--

not here--will bring you passage to your shore:

a lighter craft will have to carry you."

My guide then: "Charon, don't torment yourself:

our passage has been willed above, where One

can do what He has willed; and ask no more." (Inf., III, 88-96)

Aeneas, like Dante/pilgrim, is still in possession of his physical body also, as

Charon immediatly notices. But Charon is admonished in Aeneid - Book VI by the

Sybil in similar fashion as in Inferno by Virgil, as we see in this scene:

Now nearer to the Stygian lake they draw:

Whom, from the shore, the surly boatman saw;

Observ'd their passage thro' the shady wood,

And mark'd their near approaches to the flood.

Then thus he call'd aloud, inflam'd with wrath:

"Mortal, whate'er, who this forbidden path

In arms presum'st to tread, I charge thee, stand,

And tell thy name, and bus'ness in the land.

Know this, the realm of night--the Stygian shore:

My boat conveys no living bodies o'er...

To whom the Sibyl thus: "Compose thy mind;

Nor frauds are here contriv'd, nor force design'd...

The Trojan chief, whose lineage is from Jove,

Much fam'd for arms, and more for filial love,

Is sent to seek his sire in your Elysian grove. (Aeneid, VI, 521-545)

And Paul, as stated above, is also "alive," although there is a tendency to be

equivocal about this, as in... (my italics)

After I saw these things, I saw one of the spiritual ones coming toward me,

and he caught me in the spirit and carried me off to the third heaven.(22)

3. Presence of guide/mentor.

Dante/pilgrim is usually accompanied throughout his journey, first by the shade

of Virgil beginning in Inferno. Virgil leaves Dante/pilgrim in Purg.XXX, 49, after

which time Statius takes over for a short time before finally leaving Dante/pilgrim

alone on the banks of the Lethe, just short of the Earthly Paradise. Matilda then

takes over before finally transfering her charge to Beatrice who is his principal

guide through Paradise. In Paradiso various other figures assume a role more

closely resembling that of a mentor rather than a guide, as by this stage a spiritual

reality has supplanted the more physical character of the previous environments of

Purgatorio and Inferno.

Sybil remains by Aeneas' side throughout the journey as is confirmed in the last

few lines of the Aeneid - Book VI (my italics):

Of various things discoursing as he pass'd,

Anchises hither bends his steps at last.

Then, thro' the gate of iv'ry, he dismiss'd

His valiant offspring and divining guest. (Aeneid, VI, 1239-1242)

Paul is never without his guide in the otherworld, an un-named angel who shows

him around, chides him occasionally, and answers his questions, as in this example

when Paul is given a bird's-eye view of a large group of sinners living on earth:

I marvelled and said to the angel, "Is this the greatness of humanity?"

The angel answered and said to me, "This is it, and these are the ones

who do harm from morning till night."(23)

4. Journey begins with hell.

Inferno is the first book of Dante's Divine Comedy which includes passages of

purgatory and paradise, in that order. Dante/pilgrim approaches hell with great fear and

trepidation and this mood, tinged with episodes of personal regret and sympathy for

some (but not all) of the damned(24) lingers throughout his passage of this part of the

otherworld.

A hell of divine punishments is indicated to Aeneas as he passes through Hades,

but he doesn't linger there as he is searching for his father who dwells nearby in the

more pleasant Elysian Fields. The borders between the neighborhood of the damned

and the blessed are as distinct in the pagan underworld as they are in Dante's Christian

hell, as the Sybil explains to Aeneas:

'T is here, in different paths, the way divides;

The right to Pluto's golden palace guides;

The left to that unhappy region tends,

Which to the depth of Tartarus descends;

The seat of night profound, and punish'd fiends." (Aeneid, VI, 726-730)

The starting point of Paul's journey is somewhat confused. While he seems to go to

heaven first, he keeps his eye focused on what interests him most:

I went behind the angel, and he took me into heaven, and I looked upon the

firmament and saw there the powers: there was forgetfulness, which deceives

and draws human hearts to itself, and the spirit of slander, and the spirit of

fornication, and the spirit of wrath, and the spirit of insolence; and there were

the princes of wickedness.(25)

The last chapters of the Pauline vision, in a departure from the others, focus on hell

and its torments. Indeed, instilling terror of infernal punishment seems to be the

primary message of this work. Throughout this experience "Paul" tells the reader that

he is in an agony of despair over the fate of the poor sinners whose tortures he

describes in lurid detail for several pages while referring to himself repeatedly as the

"dearly beloved of God." So insistent is narrator "Paul" in his expressions of sympathy

for the damned that he finally manages to earn an angelic rebuke:

I sighed and wept and said, Woe to humanity! Woe to the sinners! To what

end were they born?" And the angel answered and said to me, "Why do you

weep? Are you more merciful than the Lord God who is blessed forever, who

has established the judgement and left everyone to choose good or evil of their

own will and to do as they please?"(26)

5. Purgatory or purgation.

Purgatory is a specific realm in Dante's Divine Comedy which was in keeping with

the doctrine of the Catholic Church at the time.(27) There, souls deemed worthy of

entering paradise must first purge themselves of their sins by suffering a variety of

torments according to the nature of their transgressions:

and what I sing will be that second kingdom,

in which the human soul is cleansed of sin,

becoming worthy of ascent to Heaven. (Purg. I, 4-7)

Aeneas also experiences a form of purgatory as he advances towards the meeting

with his father, especially in the emotional encounter with Dido, his suicidal former

lover. Here the hero's experience is as harrowing as Dante's with Paolo and Francesca

and, as in the encounter with Charon, reminiscent, as we see in this poignant scene of

his vain attempt at reconciliation:

Not far from these Phoenician Dido stood,

Fresh from her wound, her bosom bath'd in blood;

Whom when the Trojan hero hardly knew,

obscure in shades, and with a doubtful view,

(Doubtful as he who sees, thro' dusky night,

Or thinks he sees, the moon's uncertain light,)

With tears he first approach'd the sullen shade;

And, as his love inspir'd him, thus he said:

"Unhappy queen! then is the common breath

Of rumor true, in your reported death,

And I, alas! the cause? By Heav'n, I vow,

And all the pow'rs that rule the realms below,

Unwilling I forsook your friendly state,

Commanded by the gods, and forc'd by fate--

Those gods, that fate, whose unresisted might

Have sent me to these regions void of light,

Thro' the vast empire of eternal night.

Nor dar'd I to presume, that, press'd with grief,

My flight should urge you to this dire relief.

Stay, stay your steps, and listen to my vows:

'Tis the last interview that fate allows!"

In vain he thus attempts her mind to move

With tears, and pray'rs, and late-repenting love.

Disdainfully she look'd; then turning round,

But fix'd her eyes unmov'd upon the ground,

And what he says and swears, regards no more

Than the deaf rocks, when the loud billows roar;

But whirl'd away, to shun his hateful sight,

Hid in the forest and the shades of night;

Then sought Sichaeus thro' the shady grove,

Who answer'd all her cares, and equal'd all her love. (Aeneid VI, 610-640)

The idea of purgatory is not presented as such in the Pauline narrative but the

prototypical principle governing it (i.e., that offerings or prayers by the living might

help smooth the way for the souls of sinners) does appear in the harangue of Jesus to

the condemned on the occasion of granting them their day of rest (my italics):

Yet now because of Michael, the arcangel of my covenant, and the angels who are with him, and because of Paul, my dearly beloved whom I would not grieve, and because of your bretheren who are in the world and do offer holy gifts... I will always grant to all of you who are in torment refreshment forever for a day and a night...(28)

The idea of a hierarchical paradise, so important to Dante's vision of the otherworld,

is also found in rudimentary form in the account of Paul's vision. There is the third

heaven, the second heaven and the City of Christ, as well as some important divisions

within the latter. Paul asks his angelic guide at one point:

Is there a wall in the City of Christ more excellent in honor than this one?

The angel answered and said to me, "The second is better than the first, and

likewise the third than the second; for each one excels the other right up to the

twelfth wall." I said, "Why, lord, does one excel the other in glory? Explain it

to me." The angel answered and said to me, "Through all who have even a little

slander or envy or pride in them, something is taken from this glory, even if he

or she is in the City of Christ."(29)

6. Preoccupation with certain sins (likely the ones the subject has committed most

often).

Dante/pilgrim has more than just an inkling of his own moral shortcomings. It is

most likely the reason why he is so overwhelmed by the story of Paolo and Francesca

(Inf. V, 97-142), a parable of the risks of courtly love, himself having been an ardent

practitioner of that art. He hears their tragic tale and afterwards Virgil asks him for

his thoughts:

When I replied, my words began: "Alas,

how many gentle thoughts, how deep a longing,

had led them to the agonizing pass!" (Inf., V, 112-114)

Dante, who faints at the end of this canto, also recognizes in himself the sin of pride

for which he fears a lengthy stay on the first terrace of purgatory (where the prideful are

punished by carrying heavy stones on their backs) the next time he passes through:

I fear much more the punishment below;

my soul is anxious, in suspense; already

I feel the heavy weights of the first terrace." (Purg., XIII, 136-138)

Aeneas is not in Hades to be punished or even to be threatened with punishment

although he does suffer a form of penance for past sins there as we have already

observed. The purpose of Aeneas' voyage to the underworld is to provide him with an

experience of psychological death and rebirth and to acquaint him with his destiny in

the process, for his father Anchises, like the residents of Dante's Inferno and the Sybil,

has the ability to see the future, or at least his son's future as founder of Rome:

Thus having said, he led the hero round

The confines of the blest Elysian ground;

Which when Anchises to his son had shown,

And fir'd his mind to mount the promis'd throne,

He tells the future wars, ordain'd by fate;

The strength and customs of the Latian state; (Aeneid, VI, 1227-1232)

Other than sins of apostasy, which are punished more severely than all others in the

Pauline heaven, sins of a sexual nature seem to have pre-occupied the author or authors

with no less than fifteen separate references to "fornication" or "adultery" in a work that

is only a fraction of the size of either the Aeneid or the Divine Comedy. Here is one

example from Paul's account that combines both infractions and reminds us of the

number of corrupt clerics who also earn especially unpleasant punishments in Dante's

Inferno:(30)

Yet again I looked on the river of fire, and I saw there a man caught by the

throat by angels, keepers of hell, who had in their hands an iron with three

hooks with which they pierced that old man's entrails. I asked the angel and

said, "Lord, who is this old man upon whom such torments are inflicted?" The

angel answered and said to me, "He was a priest who did not fulfill his ministry

well, because when he was eating and drinking and whoring he offered the

sacrifice to the Lord at his holy altar."(31)

7. Specific common details of hell (i.e., darkness) and punishments (i.e., fire).

Dante describes the infernal landscape in these lines according to the medieval

convention as a place noteworthy for the absence of God's Light:

That valley, dark and deep and filled with mist,

is such that, though I gazed into its pit,

I was unable to discern a thing. (Inf., IV, 7-12)

and for its fiery punishments:

Above that plain of sand, distended flakes

of fire showered down; their fall was slow-

as snow descends on alps when no wind blows.

Just like the flames that Alexander saw

in India's hot zones, when fires fell,

intact and to the ground, on his battalions,

for which--wisely--he had his soldiers tramp

the soil to see that every fire was spent

before new flames were added to the old;

so did the never-ending heat descend;

with this, the sand was kindled just as tinder

on meeting flint will flame-doubling the pain. (Inf., XIV, 28-39)

Aeneas passes by but is made aware of

A lofty tow'r, and strong on ev'ry side

With treble walls, which Phlegethon surrounds,

Whose fiery flood the burning empire bounds;

And, press'd betwixt the rocks, the bellowing noise resounds.

Wide is the fronting gate, and, rais'd on high

With adamantine columns, threats the sky...

From hence are heard the groans of ghosts, the pains

Of sounding lashes and of dragging chains.

The Trojan stood astonish'd at their cries, (Aeneid, VI, 740-754).

Like Dante/Pilgrim and "Paul," Aeneas paused

And ask'd his guide from whence those yells arise;

And what the crimes, and what the tortures were,

And loud laments that rent the liquid air. (Aeneid, VI, 755-757).

The Pauline hell, which takes up the last three chapters of this brief but influential

piece of writing, is perhaps the first compendium of what would become the

stereotypical features of Christian otherworld torments of the damned, some of which

seem to be present in Dante's Inferno:

I saw there a river of fire burning with heat, and in it there was a multitude of

men and women sunk up to their knees, and others up to their navels; others

also up to their lips and others up to their hair;(32)

These lines are is very reminiscent of Dante's desciption of the River Phlegethon in

Inf. XII, 103-122, while

...and there were dragons entwined around their necks, shoulders and feet...(33)

reminds us of Dante's Furies in Inf. IX, 40-42.

8. The Pit of Hell as the exaltation of evil.

Dante certainly was in a climactic mood when he reached this point in his narrative,

rendering this unforgettable and evocative passage as his alter ego stares the Devil in

the face:

O reader, do not ask of me how I

grew faint and frozen then-I cannot write it:

all words would fall far short of what it was.

I did not die, and I was not alive;

think for yourself, if you have any wit,

what I became, deprived of life and death.

The emperor of the despondent kingdom

so towered from the ice, up from midchest,

that I match better with a giant's breadth

than giants match the measure of his arms;

now you can gauge the size of all of him

if it is in proportion to such parts.

Than do the giants with those arms of his;

Consider now how great must be that whole,

Which unto such a part conforms itself.

If he was once as handsome as he now

is ugly and, despite that, raised his brows

against his Maker, one can understand

how every sorrow has its source in him! (Inf. XXXIV, 22-37)

Aeneas wisely gives the depths of Tartarus a wide berth as he has no real business

there. Still, he listens enthralled as the Sybil tells of her previous journey into the

depths of Tartarus where she witnessed the worst of the infernal punishments being

meted out on the condemned:

She thus replied; "The chaste and holy race

Are all forbidden this polluted place.

But Hecate, when she gave to rule the woods,

Then led me trembling thro' these dire abodes,

And taught the tortures of th' avenging gods.

These are the realms of unrelenting fate;

And awful Rhadamanthus rules the state. (Aeneid, VI, 758-764)

The Pauline adventure has its climax in hell, as opposed to the sideshow (albeit an

important one) in the Aeneid - Book VI and the first book of Dante's Comedy. But like

Aeneas, Paul seems immune to any threat of punishment, having successfully curried

divine favor through such an exemplary conversion, we can only suppose.

9. Conversion of subject.

Dante/pilgrim is, of course, a Christian throughout, although a wayward one. His

supreme moment of catharsis, however comes at the end of his journey as he stares into

the face of God. Again, he reminds us that words are not adequate, but boldly states

nevertheless, that

From that point on, what I could see was greater

than speech can show: at such a sight, it fails-

and memory fails when faced with such excess.

As one who sees within a dream, and, later,

the passion that had been imprinted stays,

but nothing of the rest returns to mind,

such am I, for my vision almost fades

completely, yet it still distills within

my heart the sweetness that was born of it. (Par., XXXIII, 55-63)

So, having seen the un-seeable and known the un-knowable, Dante/pilgrim is

changed forever, even though he admits he can't fully explain it.

Aeneas leaves Hades also changed forever, re-born and effectively converted

from an aimless wanderer to the captain of his own great personal destiny:

Thus having said, the father spirit leads

The priestess and his son thro' swarms of shades,

And takes a rising ground, from thence to see

The long procession of his progeny.

"Survey," pursued the sire, "this airy throng,

As, offer'd to thy view, they pass along.

These are th' Italian names, which fate will join

With ours, and graff upon the Trojan line. (Aeneid, VI, 1021-1028)

"Paul" has already converted apparently(34) but in this narrative he is portrayed as

pleading for one last chance at conversion for the damned. One day of respite for their

tortured souls is the best he can manage, according to these words spoken by the

"angels of torment" and the "evil angels":

"This is the judgement of God on those that did not have mercy. Yet you have

received this great grace, refreshment for the night and day of the Lord's Day,

because of Paul, the dearly beloved of God who has come down to you"(35)

10. Changing environmnent as subject moves away from hell towards heaven.

In as much as the environment of Dante's Inferno became progressively worse with the descent of the protagonist into it, Dante/poet here informs his readers that they can expect things to improve quickly as the evil place fades and the fairer Island of Purgatory rises into view:

To course across more kindly waters now

my talent's little vessel lifts her sails,

leaving behind herself a sea so cruel; ( Purg., I, 1-3)

In the last few lines of the Aeneid - Book VI, Aeneas is out of Hades and sailing

along under presumably blue Mediterranean skies:

Straight to the ships Aeneas took his way,

Embark'd his men, and skimm'd along the sea,

Still coasting, till he gain'd Cajeta's bay.

At length on oozy ground his galleys moor;

Their heads are turn'd to sea, their sterns to shore. (Aeneid, VI, 1243-1247)

In the Pauline narrative there is less a continuing sense of movement in one

direction as a back-and-forth situation alternating between the blessed and the damned.

I suggest that this inconsistent shifting point of view might reflect confusion on the part

of the writer or writers rather than a deliberate plan.

11. Enlightenment of visionary.

Dante's eyes are opened as never before in the brilliance of God's Light...

But then my mind was struck with light that flashed

And, with this light, received what it had asked. (Par., XXXIII,

140-141)

although he admits to some difficulty in recalling it,

What little I recall is to be told,

from this point on, in words more weak than those

of one whose infant tongue still bathes at the breast. (Par., XXXIII,

106-108)

He tries nonetheless:

In its profundity I saw-ingathered

and bound by love into one single volume-

what, in the universe, seems separate, scattered:

substances, accidents, and dispositions

as if conjoined-in such a way that what

I tell is only rudimentary.

I think I saw the universal shape

which that knot takes; for, speaking this, I feel

a joy that is more ample. That one moment

brings more forgetfulness to me than twenty-

five centuries have brought to the endeavor

that startled Neptune with the Argo's shadow! (Par., XXXIII, 91-

96)

Aeneas, too, has left Hades a changed and wiser man, although we have only

the implication of what he experienced there that we must intuit rather than any

specific reflections that Virgil puts down to him in the Aeneid.

The Pauline narrative gives us no information of Paul's life after his visit, but

from his gospel writings we know that the experience of a vision marked the

beginning of his Christian life (See note 31).

12. Return to a new life.

Dante ends his tale with only the implication and expectation of his life

continuing on earth (for only a short time as historical record confirms) but in

Paradiso the writer refers matter-of-factly to his safe return:

In Heaven's court, from which I have returned,

one finds so many rare and precious gems

that are not to be taken from that kingdom: (Par., X, 70-72).

and for good measure has none other than St. Peter vouchsafe it:

and you, my son, who through your mortal weight

will yet return below, speak plainly there,

and do not hide that which I do not hide." (Par., XXVII, 64-66)

Later on he has his crusading ancestor Cacciaguida offer some encouraging words

as to the poet's time of mortal life remaining:

Yet I'd not have you envying your neighbors;

your life will long outlast the punishment

that is to fall upon their treacheries." (Par., XVII, 97-99)

Aeneas is born again through his other-wordly experience emerging dedicated

to a new set of tasks which inspire him to hasten to Latium and get on with his busy

life. Significantly his aged nurse Caieta dies enroute and is buried with full honors

ashore, symbolizing the death of the hero's former life as a Trojan:

And Thou, O matron of eternal fame,

Here dying to the shore has left thy name:

"Caieta" still the place is called from thee,

The nurse of great Aeneas' infancy.

Here rest thy bones in great Hesperia's plains;

Thy name ('tis all a ghost can have) remains. (Aeneid, VII, 1-6)

4. Conclusion

The journey to the realm beyond mortal life in Dante's Divine Comedy

exemplifies a popular theme that has inspired writers from a variety of cultures

across the ages. These writers have ranged from a few extremely gifted and well-known individuals to numerous anonymous ghostwriters whose real identity has

been lost but whose works, such as they are, have survived as popular folklore if

not as literature.

Possible reasons for the durability of many works dealing with this theme

include: 1) the didactic value they possess to the aims of the Christian Church; 2)

the apparent psychological appeal that stories of the realm beyond the plane of

mortal existence hold for readers--especially stories that elucidate the concept of

hell and the punishments of the damned; 3) the outstanding literary quality of a

certain few of these works, such as Virgil's Aeneid, Homer's Oddysey and Iliad ,

and Dante's Divine Comedy.

Dante doubtless found inspiration for his mighty epic in many quarters, not least in

the deep well of his own creative soul. It is perhaps unfair to compare his lavish Divine

Comedy with such a poor thing that is (in literary terms at least) the anonymous,

abbreviated, and catechistical work known as The Vision of Saint Paul--but sometimes

great inspiration comes in plain packages. As the Aeneid, the purportedly

autobiographical story of Paul's vision/journey very likely provided Dante with some

ideas of structure and scenery but without earning the overt praise and homage that he

heaped upon the well-deserving epic poem of his literary idol of Rome's Golden Age,

Virgil.

Another possible reason Dante might have had for not wanting to draw too much attention to the Pauline work is its vision of imminent apocalypse. This was perhaps a source of uneasiness to some Christian thinkers as the expected event had become rather painfully overdue by the time of Dante. In any case, Dante achieved great success in grafting his own cosmological and theological vision of the otherworld onto the tradition commenced by Homer and continued by Virgil, in literary terms, and also in the obvious and enduring influence his Divine Comedy had on the popular mythos of contemporary medieval as well as later Christian society.

Bloomfield, Maurice. The Religion of the Veda. New York: AMS Press,

Inc., 1969.

Bonner, H. B. The Christian Hell. London: Watts & Co., 1913.

Boswell, C.S. An Irish Precursor of Dante. London: David Nutt, 1908.

Clarke, Howard. Vergil's Aeneid and Fourth ("Messianic") Eclogue in the

Dryden Translation. University Park: Pennsylvania State University

Press,1989.

Gardner, Eileen (Ed.), Visions of Heaven & Hell Before Dante. New York:

Italica Press, Inc., 1989.

Le Goff, Jacques. The Birth of Purgatory. Trans. Arthur Goldhammer. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1984.

Mandelbaum, Allen. The Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri - I. Inferno,

II.Purgatorio, III. Paradiso. New York: Bantam Books, 1982.

Matsunaga, Daigan & Alicia. The Buddhist Concept of Hell. New York:

The Philosophical Library, 1972.

Lang, Bernhard., McDannell, Colleen. Heaven - A History - New Haven:

Yale University Press, 1988.

Miller, Jeanine. The Vedas - Harmony, Meditation and Fulfilment. London:

Rider & Co.,1974.

Pagels, Elaine. The Origin of Satan. New York: Random House, 1995.

Holy Bible, King James Version.

Singleton, Charles S. The Divine Comedy; Inferno; 2. Commentary.

Princeton: Princeton University Press,1970.

1. See Eileen Gardner, Medieval Visions of Heaven and Hell--A Sourcebook, (New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1993).

2. Eileen Gardner (Ed.), Visions of Heaven & Hell Before Dante (New York: Italica Press, Inc., 1989), xxviii, xxx; and, C.S. Boswell, An Irish Precursor of Dante, (London: David Nutt, 1908), 1-2.

3. Charles S. Singleton, The Divine Comedy; Inferno; 2. Commentary (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1970), 26

4. Gardner, Medieval Visions of Heaven and Hell--A Sourcebook, xxviii

5. Hypatia Bradlaugh Bonner, The Christian Hell (London: Watts & Co, 1913), 16. Bonner's comment brings to mind Mark Twain's famous quip on this subject, i.e., that he preferred, "...Heaven for the climate but Hell for the company."

6. Daigan & Alicia Matsunaga, The Buddhist Concept of Hell (city: The Philosophical Library,1972), 13. In The Vedas - Harmony, Meditation and Fulfilment, Rider & Co., 1974, 161, Jeanine Miller suggests that these passages (Rgv VII.104 and Rgv II.29) are a rather vindictive incantation directed more towards "demons and very evil men"(7)

7. Jeanine Miller, The Vedas - Harmony, Meditation and Fulfilment (city: Rider & Co.,1974), 161

8. Maurice Bloomfield, Religion of the Veda (city: AMS Press, Inc., 1969), 252.

9. Ibid., 260.

10. Matsunaga, The Buddhist Concept of Hell, 39.

11. Ibid., 43.

12. Colleen McDannell, Bernard Lang, Heaven - A History (New Haven and London:Yale University Press, 1988), 3.

13. Elaine Pagels, The Origin of Satan (New York: Random House, 1995), 57-58.

14. Ibid., 61.

15. Ibid., 39.

16. Bonner, The Christian Hell, 46-48.

17. Gardner, Medieval Vision of Heaven and Hell--A Sourcebook, 179.

18. In the process of being re-vamped to Christian requirements hell eventually become entirely too harsh a place according to some, like Hypatia Bradlaugh Bonner. A disgruntled hell-basher of the Victorian Age, Bonner gives Dante scholarship short shrift in her angry work of occasionally hysterical tone, The Christian Hell (London: Watts & Co.), 1913, 32, and goes on to accuse Christianity of "surpassing horror" in its construction of an infernal realm that reaches "...a pinnacle of ferocity and moral insensibility never attained before or since in any religion known to mankind." I suggest that Bonner represents a noteworthy point in the scale of popular reaction to the concept of hell as represented by the Church, Dante, and other writers throughout the Christian era--perhaps one of the first modern writers to utterly reject the orthodox view on humanistic and rational grounds.

19. Gardner (Ed.), Visions of Heaven and Hell Before Dante, xv-xx.

20. The tone of this work differs significantly from that of II Corinthians where Paul discusses rather obliquely what he might have experienced in such a vision (a fact only to be expected from the ghostwritten forgery that is The Vision of St. Paul). The cursory treatment of Paul's vision/journey in II Corinthians, however, was doubtless the inspiration for the later detailed version that enjoyed such great popularity.

21. Ibid., 14

22. Ibid., 18. A shifting point-of-view is a continuing problem in this work, as will be discussed further on.

23. Ibid., 19-20.

24. E.g.,when Dante pilgrim encounters the shades of the star-crossed lovers Paolo and Francesca in Inf. V, he is so overcome with grief that he faints. But, when he encounters Filippo Argenti (Inf. VIII), his arch-enemy from the still sore subject of his experience of Florentine political life, his rancor and thirst for revenge more resemble the God of the Old Testament. This pattern is repeated many times throughout Inferno with Dante's least favorites often showing up in the most uncomfortable circumstances.

25. Ibid., 18.

26. Ibid., 42.

27. Eileen Gardner, Medieval Visions of Heaven and Hell--A Sourcebook (New York: Garland Publishing, Inc.), 1993, xvii. The existence of Purgatory is still a feature of Roman Catholic theology. For a detailed discussion of the subject of purgatory see also Jacques Legoff, The Birth of Purgatory (Chicago: Chicago University Press, trans. Arthur Goldhammer), 1984.

28. Ibid., 46.

29. Ibid., 36. Here may well be found the source of Dante's inspiration for the otherworld hierarchy that extends even into heaven where, depending on their place in the Empyrean, Beatrice explains, "...some souls sense the Eternal Spirit more--some less." (Par. IV, 35-36).

30. To whit, Filippo Argenti (Inf., VIII), Pope Anastius (Inf., XI, 8), Andrea dei Mozzi (Inf., XV, 112), Pope Nicholas III (Inf., XIX), Catalano and Loderingo (Inf., XXIII, 103), Guido da Montefeltro (Inf., XXVII), just to name a few, and a host of unknowns whose "undiscerning life that made them filthy now renders them unrecognizable." (Inf., VII, 53-54). Given his demonstrated apetite for revenge upon his enemies Dante was denied what would have doubtless been the personal frisson of seeing his arch-nemesis Boniface III expire before he finished his Comedy.

31. Gardner, Visions of Heaven and Hell Before Dante, 37-38.

32. Ibid., 36.

33. Ibid., 41.

34. The Pauline narrative gives us no information of Paul's life after his visit to heaven and hell, but from his New Testament writings (which authorship is in less dispute) we are given the impression that a visionary experience marked the beginning of his Christian life. The Vision of St. Paul narrative thus poses a problem in that it does not explain why a recent convert is accorded such deference and at the same time seems to be so well connected in heaven.

35. Gardner, Visions of Heaven and Hell Before Dante, 46.

Back to The Soul of a Writer Page